The History of Seed Oils

In the early 1900s, Americans didn’t eat seed oils. Soybean, corn, canola, and sunflower oil were agricultural waste products, not food. But today, they make up more than 20% of the average American’s daily calories.

What happened?

The story begins, strangely enough, with soap.

In the 1830s, two brothers-in-law, William Procter and James Gamble, founded a soap and candle company in Cincinnati. Back then, soap was made from rendered animal fat. But the men eventually realized they could cut costs by replacing expensive animal fats with cottonseed oil, a cheap waste product of the cotton industry.

Bitter to the taste and laced with gossypol (a natural phytochemical once used as male birth control in China), cottonseed oil was nowhere close to entering our food supply. But things changed in 1907 when Procter & Gamble bought the rights to a new German chemical process called hydrogenation that could turn liquid oils into solid fats. P&G’s initial aim was to produce a solid fat for soapmaking. But they soon realized it created a substance that looked a lot like lard, the default cooking fat in every American kitchen.

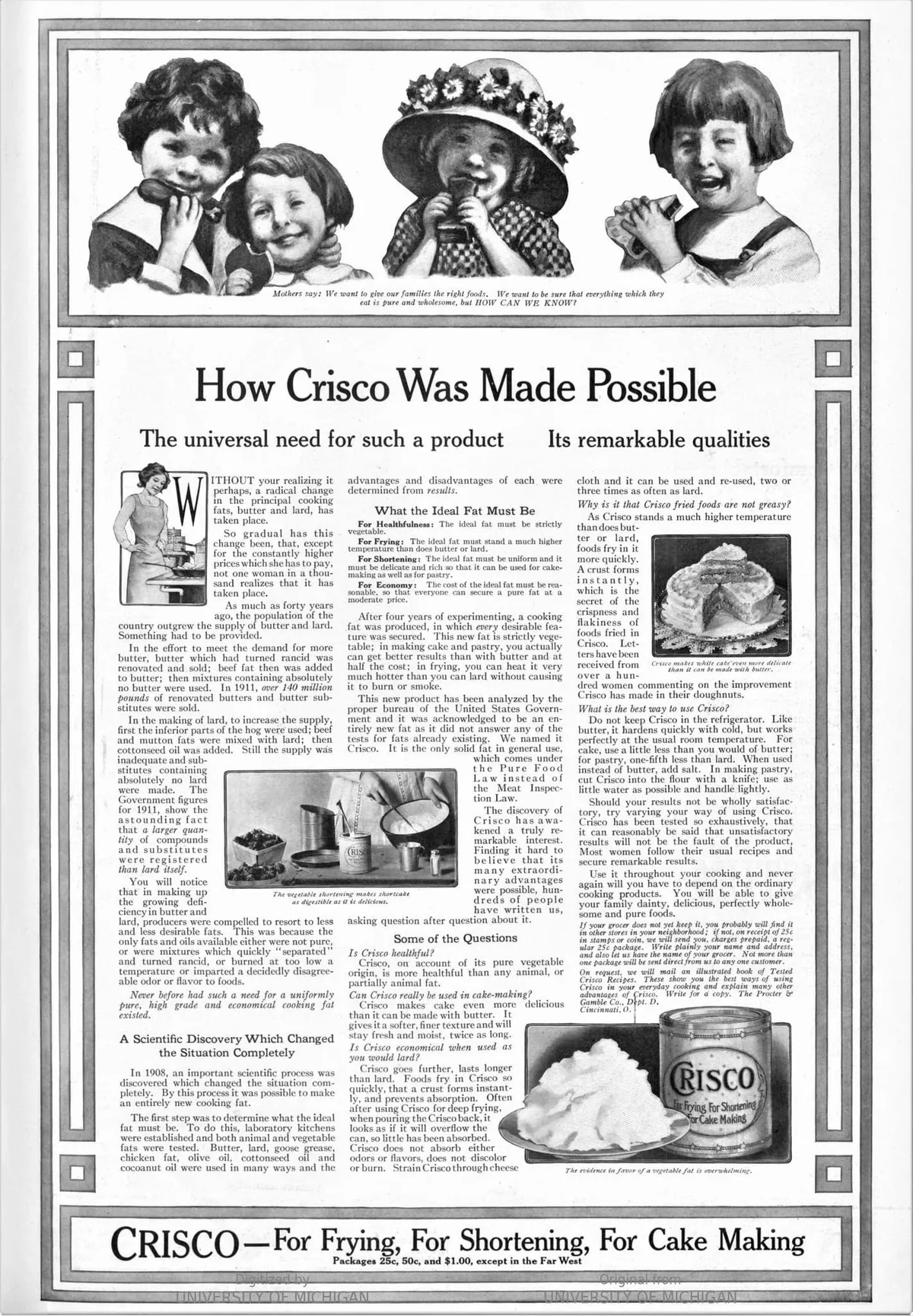

The company saw a new market opportunity and patented it as a food product. They called it Crisco—short for “crystallized cottonseed oil”—and launched a massive advertising campaign to put it in American homes. They hired the J. Walter Thompson ad agency to position Crisco as a modern, scientific alternative to traditional fats and ran ads like this one in the Ladies’ Home Journal that made unsubstantiated claims like, “Crisco, on account of its pure vegetable origin, is more healthful than any animal fat.”

Advertisement for Crisco in the Ladies’ Home Journal in 1912 (Digitized by the University of Michigan)

Advertisement for Crisco in the Ladies’ Home Journal in 1912 (Digitized by the University of Michigan)

The strategy worked. In 1912, Americans bought 2.6 million pounds of Crisco. By 1916, they were buying 60 million. A waste product had become a pantry staple.

This opened the door for other oils. By the 1930s, soybeans proved more efficient for producing oil than cottonseed, and quickly became the top choice for food companies. Corn, canola, safflower oils followed. They were cheap, shelf-stable, and easy to produce in large quantities. As long as they were marketed as healthy, people bought in.

Then in 1961, the American Heart Association (AHA) made a historic recommendation. They told Americans to replace saturated fats in their diet with polyunsaturated fats from vegetable oils. It was the first time a major health group advised the American public to change its diet to prevent heart disease.

The impact was enormous. As journalist Nina Teicholz later put it: “The 1961 AHA advice to limit saturated fat is arguably the single-most influential nutrition policy ever published.” It came to be adopted by the U.S. Government as official policy for all Americans in 1980, and then by governments around the world.

Teicholz also points out an unsettling conflict of interest: in 1948, Procter & Gamble donated $1.7 million to the AHA (roughly $20 million today). That gift helped transform the organization from a small group of cardiologists into the most powerful voice on heart disease in the country.

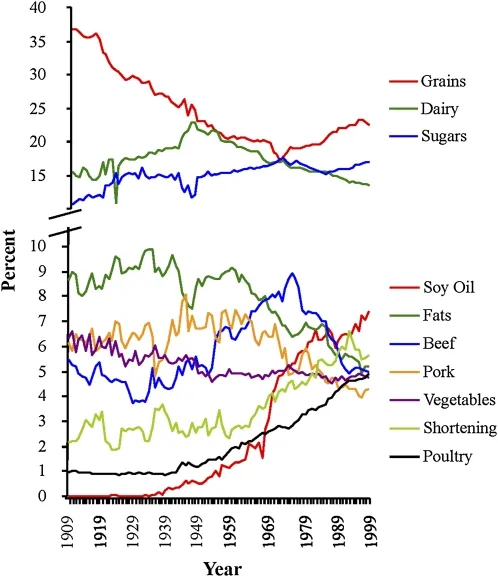

Following the AHA’s endorsement, vegetable oil and shortening consumption exploded (see chart below). Crisco, once sold as a cooking innovation, was now a health food.

Major sources of calories between 1909 and 1999. (Crisco is a vegetable oil-based shortening). Source: Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century

Major sources of calories between 1909 and 1999. (Crisco is a vegetable oil-based shortening). Source: Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century

It’s easy to see how conspiracy theories took root: the world’s largest vegetable oil producer funds the AHA, and a few years later the AHA tells Americans to eat more vegetable oil. But the full story is likely a bit more nuanced.

By the 1950s, heart disease had become the leading cause of death in America, and the medical community was urgently searching for answers. The “diet-heart hypothesis” offered one. It proposed that eating saturated fat raised cholesterol, which in turn caused heart disease.

The theory was championed by Ancel Keys, a charismatic physiologist who became interested in heart disease after World War II. He noticed that heart disease rates had dropped in parts of Europe hit hardest by food shortages. In 1947, Keys launched a study of 286 Minnesota businessmen and found a correlation between high cholesterol and heart disease. In 1953, he formally proposed that saturated fat was to blame.

Not everyone agreed. At a 1955 World Health Organization meeting in Geneva, experts dismissed Keys’s evidence as weak. Two years later, Dr. Herman Hilleboe and Dr. Jacob Yerushalmy—both prominent public health figures of their time—published a pointed critique arguing that Keys had cherry-picked countries to support his theory and failed to prove causation. “No matter how plausible such an association may appear,” they wrote, “it is not in itself proof of a cause-effect relationship.”

It didn’t matter. Keys was relentless and already had a powerful ally: Dr. Paul Dudley White, a co-founder of the AHA and one of the most respected cardiologists in the country.

White helped Keys organize his famous Seven Countries Study, and often joined him on overseas research trips. Decades later, this study would also be criticized for excluding countries that didn’t support Keys’s hypothesis. For example, France (which had a high intake of saturated fat but relatively low rates of heart disease) was not included.

White didn’t co-author Keys’s papers, but he used his reputation to amplify Keys’s ideas. Where Keys brought data, White brought credibility.

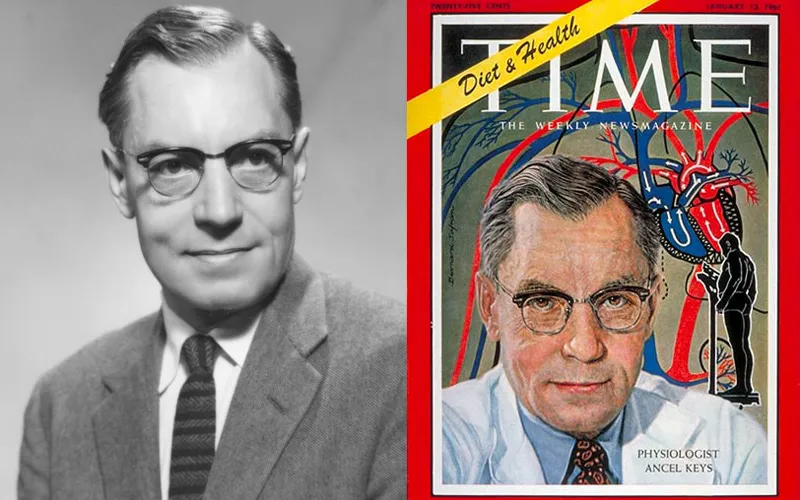

In 1961, White secured Keys a seat on the AHA’s Nutrition Committee, and the AHA officially endorsed the diet-heart hypothesis that same year. Two weeks later, Time magazine put Keys on the cover, guaranteeing him international celebrity status and effectively endorsing his views.

Ancel Keys on the cover of Time Magazine in 1962

Ancel Keys on the cover of Time Magazine in 1962

However, public opinion might not have shifted so quickly without one very public event: President Eisenhower’s heart attack in 1955. The news stunned the nation and made heart disease a front-page issue. White was brought in to help manage Eisenhower’s care.

During Eisenhower’s recovery, White held a televised press conference where he told Americans that lifestyle factors like poor diet, smoking, and lack of exercise could significantly increase the risk of heart attacks. He even suggested that Eisenhower’s fondness for butter and red meat might have played a role in his condition. And in a front-page New York Times article, the only researcher White mentioned by name was Ancel Keys.

Eisenhower obediently followed his doctor's orders. He quit smoking, stopped eating butter, avoided red meat, and became a poster child for the low-fat movement. It wasn’t just scientists now. It was the president himself.

This convergence of science, celebrity, and media gave the diet-heart hypothesis tremendous momentum, and by the mid-1960s, few questioned the idea that saturated fat was dangerous and vegetable oil was healthy.

President Eisenhower's (right) relationship with White (left) reportedly cooled after Eisenhower began to suspect that White was too eager for publicity.

President Eisenhower's (right) relationship with White (left) reportedly cooled after Eisenhower began to suspect that White was too eager for publicity.

However, despite his strict adherence to the low-fat diet, Eisenhower died of congestive heart failure a decade later. White too died of a heart attack. It turns out there was something the AHA and Keys had overlooked: trans fat.

Hydrogenating oil doesn’t just make it solid. It also twists the molecular structure. The result is a kind of fat that the human body has no evolutionary blueprint to handle. Harvard’s School of Public Health summarizes the health effects plainly:

“Trans fatty acids, more commonly called trans fats, are made by heating liquid vegetable oils in the presence of hydrogen gas and a catalyst, a process called hydrogenation… Trans fats are the worst type of fat for the heart, blood vessels, and rest of the body because they: [1] Raise bad LDL and lower good HDL. [2] Create inflammation—a reaction related to immunity— which has been implicated in heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and other chronic conditions. [3.] Contribute to insulin resistance. [4.] Can have harmful health effects even in small amounts – for each additional 2 percent of calories from trans fat consumed daily, the risk of coronary heart disease increases by 23 percent.”

But nobody knew that in the 1960s.

One man did suspect it. Dr. Fred Kummerow, a biochemist at the University of Illinois, studied the arteries of heart attack victims in the 1950s and noticed they weren’t just clogged with cholesterol—they contained large amounts of trans fats.

He followed up with animal studies, and observed that pigs fed a diet high in these artificial fats quickly developed the same artery-clogging plaque seen in humans. But when he published his findings in 1957, it was dismissed on the basis that his research had been conducted on animals, which sometimes react differently than humans do.

Fred A. Kummerow in 2013 at the University of Illinois. His own diet, he said, included red meat, whole milk and egg scrambled in butter. He died in 2017 at the age of 102.

Fred A. Kummerow in 2013 at the University of Illinois. His own diet, he said, included red meat, whole milk and egg scrambled in butter. He died in 2017 at the age of 102.

Kummerow’s work was ignored for decades while trans fats become even more entrenched in the American diet.

“In the 1960s and ‘80s the processed food industry, enjoying a cozy relationship with scientists, played a large role in keeping trans fats in people’s diets,” Kummerow reflected in a 2016 New York Times interview.

For example, the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), described Burger King’s switch to hydrogenated oils in 1986 as a “great boon to Americans’ arteries.”

But Kummerow persisted and gradually won over key members of the scientific establishment.

In 1993, Dr. Walter Willett, a leading epidemiologist and nutrition professor at Harvard, published a major study linking trans fats to coronary heart disease. His team found that replacing just 2% of calories from trans fats with healthy unsaturated fats could cut heart disease risk by roughly one-third. It was a breakthrough moment, and Willett credited Kummerow’s work as an inspiration.

An influential symposium on trans fat later in the 1990s drew public attention to the issue, but it still took until 2006 for the FDA to rule that trans fats must be declared on Nutrition Facts labels. And only in 2015—after Kummerow filed a petition and sued the FDA—did the agency rule that hydrogenated oils are no longer “generally recognized as safe” for use in human food. By then, Kummerow was 101 years old.

Manufacturers were given three years to comply. But rather than return to natural fats, many companies switched to “fully hydrogenated” oils, which undergo an extra chemical step to eliminate trans fats. These products can legally carry a “zero trans fat” label, but they're still ultra-processed.

Which brings us to today. We replaced butter with margarine, tallow with soybean oil, and milk with almond and oat emulsions—all under the assumption that these choices were healthier. But as the science shifted, our habits didn't. Seed oils still account for more than a fifth of our calories, and many people still think saturated fat is the enemy.

Kummerow drank whole milk, ate red meat, and scrambled his eggs in butter. He lived to 102. Maybe he was lucky. Or maybe there’s something to be said for eating foods that don’t require a chemistry degree to understand.